The Seven Most Asked Typescript Questions on StackOverflow — Explained

I hate Stackoverflow — said no developer.

While it’s helpful to have your answers a Google search away, what’s powerful is truly understanding the solutions you stumble on.

In this article, I’ll explore the seven most stackoverflowed Typescript questions.

I spent hours researching these.

I hope you gain a deeper understanding of the common problems you may face with Typescript.

This is also relevant if you’re just learning Typescript — what better way than to get familiar with your future challenges!

Let’s get right into it.

Table of contents

- What is the difference between Interfaces vs Types in Typescript?

- In Typescript, what is the ! (exclamation mark / bang) operator?

- What is a “.d.ts” file in TypeScript?

- How Do You Explicitly Set a New Property on ‘window’ in Typescript?

- Are Strongly Typed Functions as Parameters Possible in Typescript?

- How to Fix Could Not Find Declaration File for Module …?

- How Do I Dynamically Assign Properties to an Object in Typescript?

Note: You can get a PDF or ePub, version of this cheatsheet for easier reference, or for reading on your Kindle or tablet.

1. What is the difference between Interfaces vs Types in Typescript?

The interfaces vs types (technically, type alias) conversation is a well contested one.

When beginning Typescript, you may find it confusing to settle on a choice. This article clears up the confusion and helps you choose which is right for you.

TLDR

In numerous instances, you can use either an interface or type alias exchangeably.

Almost all features of an interface are available via type aliases, except you cannot add new properties to a type by re-declaring it. You must use an intersection type.

Why the Confusion in the first place

Whenever we’re faced with multiple options, most people begin to suffer from the paradox of choice.

In this case, there are just two options.

What’s so confusing about this?

Well, the main confusion here stems from the fact that these two options are so evenly matched in most regards.

This makes it difficult to make an obvious choice — especially if you’re just starting out with Typescript.

A Basic Example

Let’s get on the same page with quick examples of an interface and a type alias.

Consider the representations of a Human type below:

// type

type Human = {

name: string

legs: number

head: number

}

// interface

interface Human {

name: string

legs: number

head: number

}

These are both correct ways to denote the Human type, i.e., via a type alias or an interface.

The differences between Type alias and Interfaces

Below are the main differences between a type alias and an interface:

Key difference: interfaces can only describe object shapes. Type aliases can be used for other types such as primitives, unions and tuples.

A type alias is quite flexible in the data types you can represent. From basic primitives to complex unions and tuples, as shown below:

// primitives

type Name = string

// object

type Male = {

name: string

}

type Female = {

name: string

}

// union

type HumanSex = Male | Female

// tuple

type Children = [Female, Male, Female]

Unlike, type aliases, you may only represent object types with an interface.

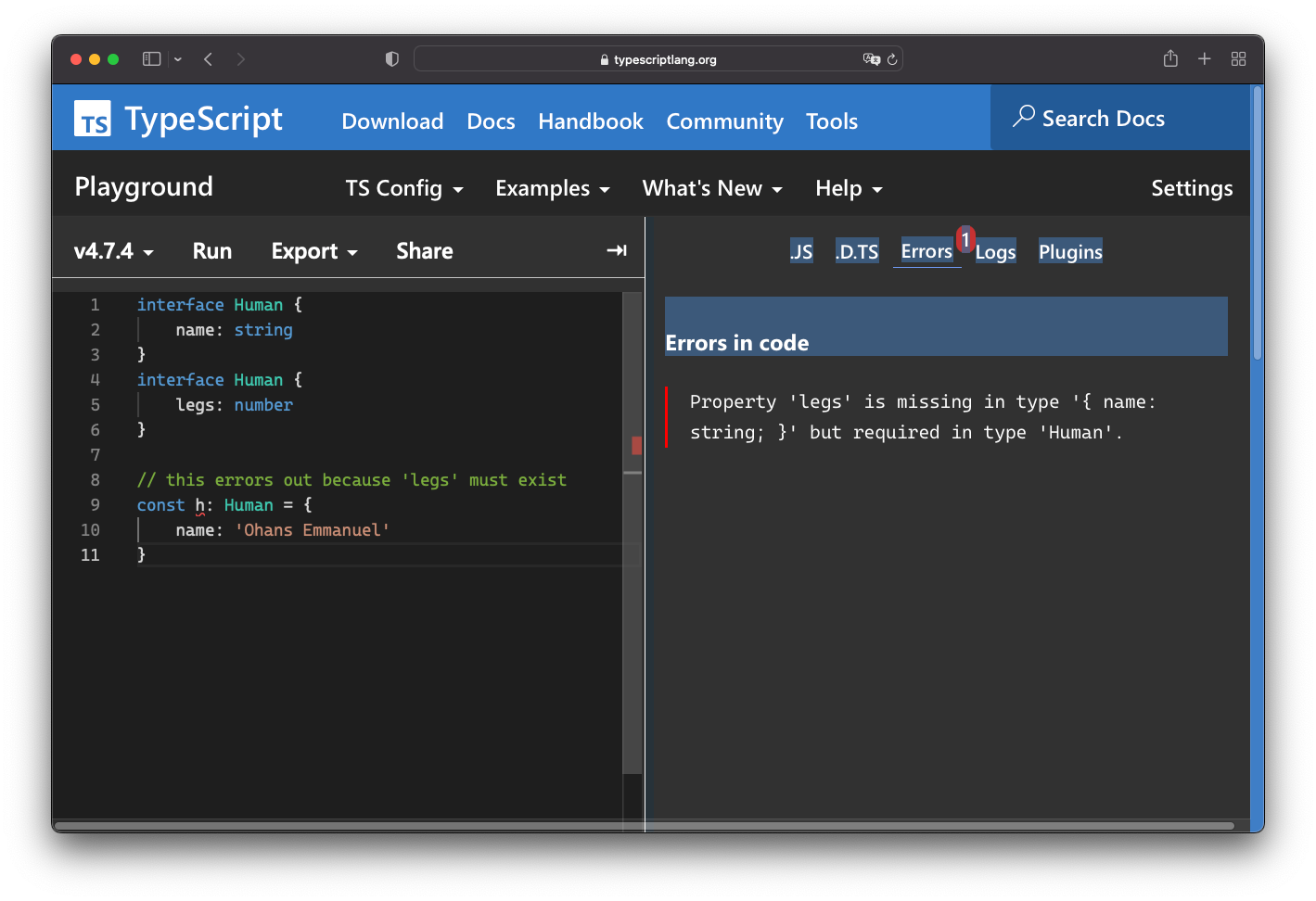

Key difference: interfaces can be extended by declaring it multiple times

Consider the following example:

interface Human {

name: string

}

interface Human {

legs: number

}

The two declarations above will become:

interface Human {

name: string

legs: number

}

Human will be treated as a single interface: a combination of the members of both declarations.

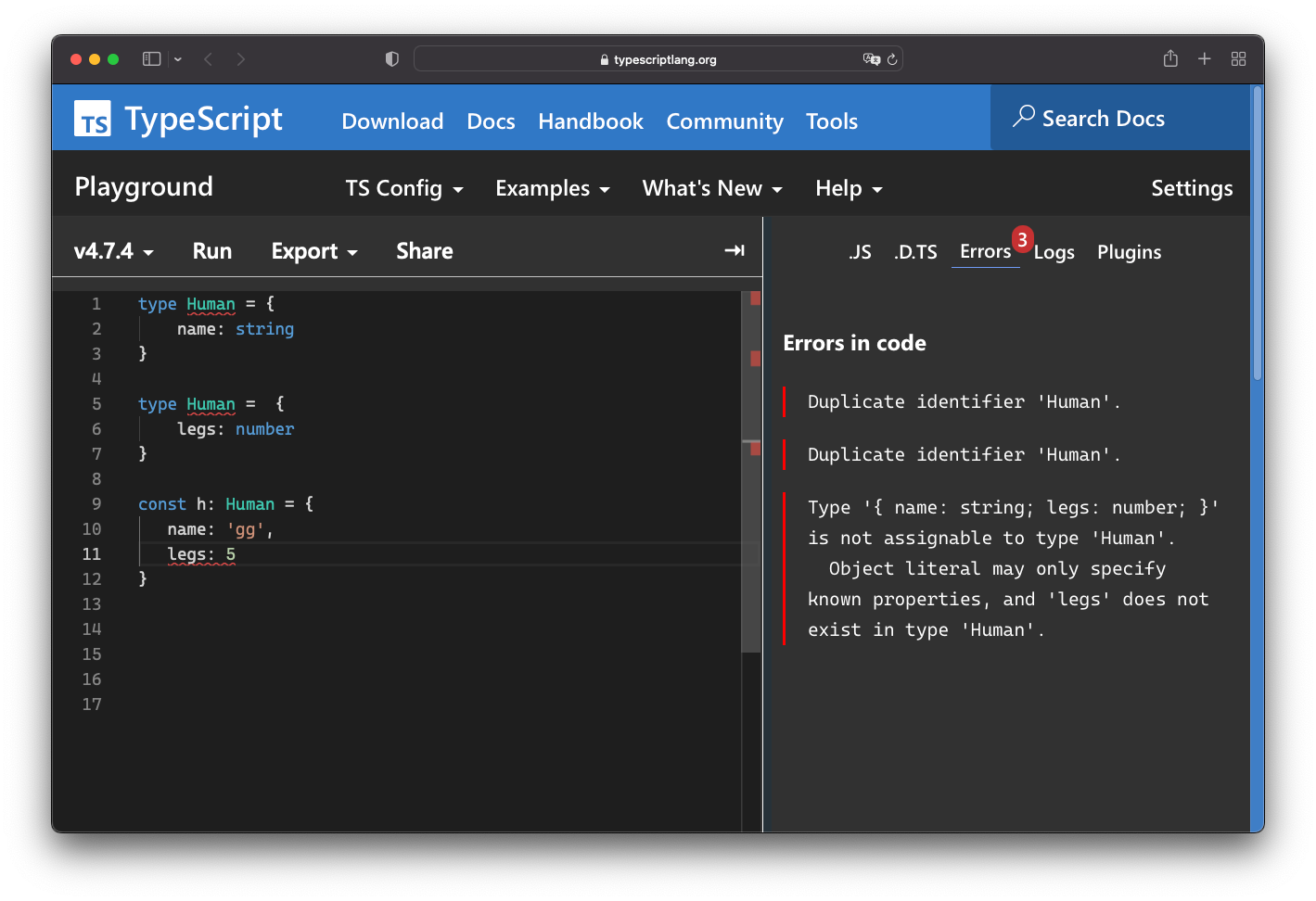

This is not the case with type aliases.

With a type alias, the following will lead to an error:

type Human = {

name: string

}

type Human = {

legs: number

}

const h: Human = {

name: 'gg',

legs: 5

}

With Type aliases, you’ll have to resort to an intersection type:

type HumanWithName = {

name: string

}

type HumanWithLegs = {

legs: number

}

type Human = HumanWithName & HumanWithLegs

const h: Human = {

name: 'gg',

legs: 5

}

Minor difference: Both can be extended, but with different syntaxes

With interfaces, you use the extends keyword. For types, you must use an intersection.

Consider the following examples:

Type alias extends type alias

type HumanWithName = {

name: string

}

type Human = HumanWithName & {

legs: number

eyes: number

}

Type alias extends an interface

interface HumanWithName {

name: string

}

type Human = HumanWithName & {

legs: number

eyes: number

}

Interface extends interface

interface HumanWithName {

name: string

}

interface Human extends HumanWithName {

legs: number

eyes: number

}

An interface extends a type alias

type HumanWithName = {

name: string

}

interface Human extends HumanWithName {

legs: number

eyes: number

}

As you can see, this is not particularly a reason to choose one over the other. However, the syntaxes differ.

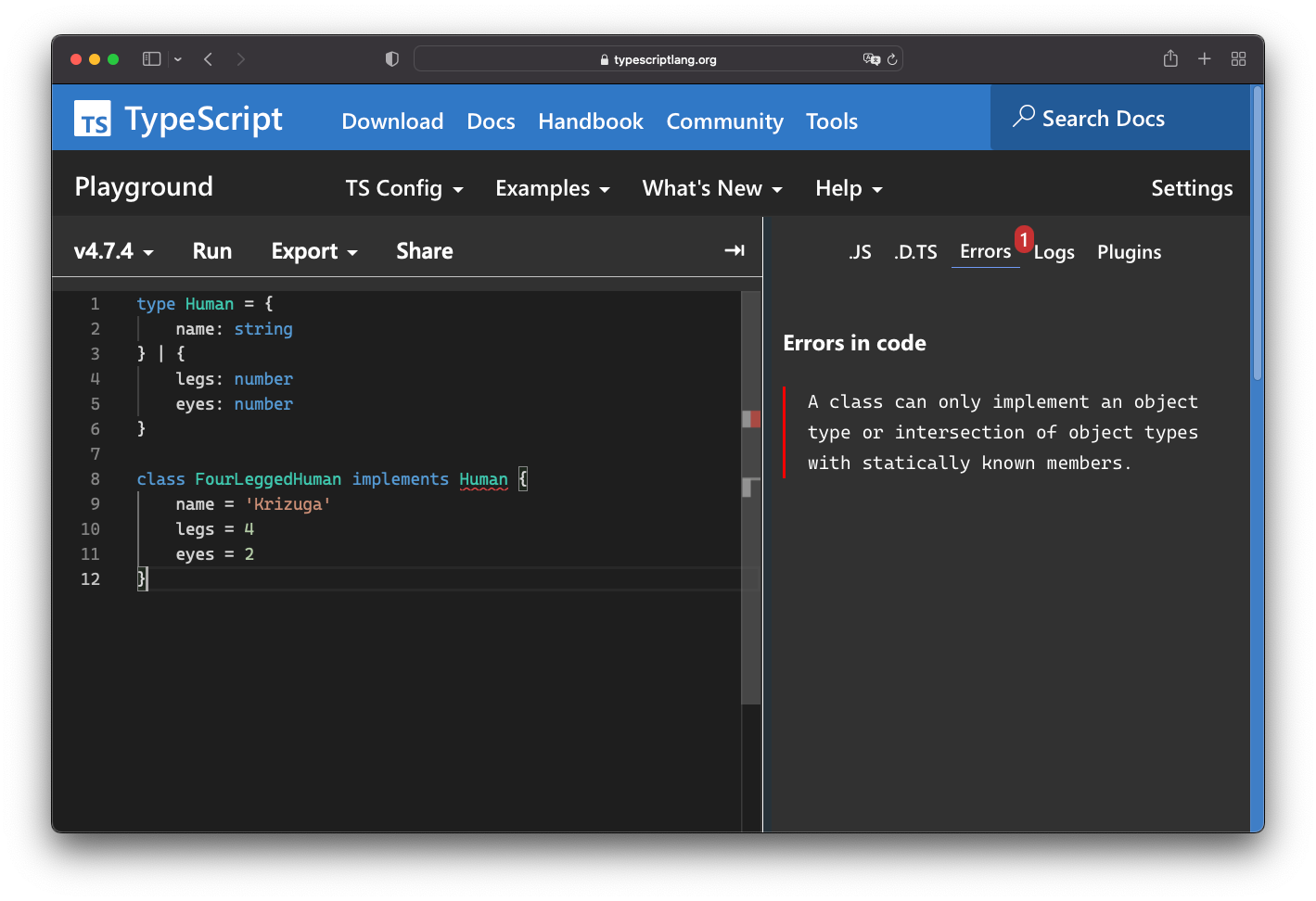

Minor difference: classes can only implement statically known members

A class can implement both interfaces or type aliases. However, a class cannot implement or extend a union type.

Consider the following example:

Class implements interface

interface Human {

name: string

legs: number

eyes: number

}

class FourLeggedHuman implements Human {

name = 'Krizuga'

legs = 4

eyes = 2

}

Class implements type alias

type Human = {

name: string

legs: number

eyes: number

}

class FourLeggedHuman implements Human {

name = 'Krizuga'

legs = 4

eyes = 2

}

Both these work without any errors. However, the following fails:

Class implements union type

type Human = {

name: string

} | {

legs: number

eyes: number

}

class FourLeggedHuman implements Human {

name = 'Krizuga'

legs = 4

eyes = 2

}

Summary

Your mileage may differ, but wherever possible, I stick to type aliases for their flexibility and simpler syntax, i.e., I pick type aliases except I specifically need features from an interface.

For the most part, you can also decide based on your personal preference, but stay consistent with your choice — at least in a single given project.

For completeness, I must add that in performance critical types, interface comparison checks can be faster than type aliases. I’m yet to find this to be an issue.

2: In Typescript, what is the ! (exclamation mark / bang) operator?

TLDR

This is technically called the non-null assertion operator. If the typescript compiler complains about a value being null or undefined, you can use the ! operator to assert that the said value is not null or undefined.

Personal take: avoid doing this wherever possible.

What is the non-null assertion operator?

null and undefined are valid Javascript values.

The statement above holds true for all Typescript applications as well.

However, Typescript goes one step further.

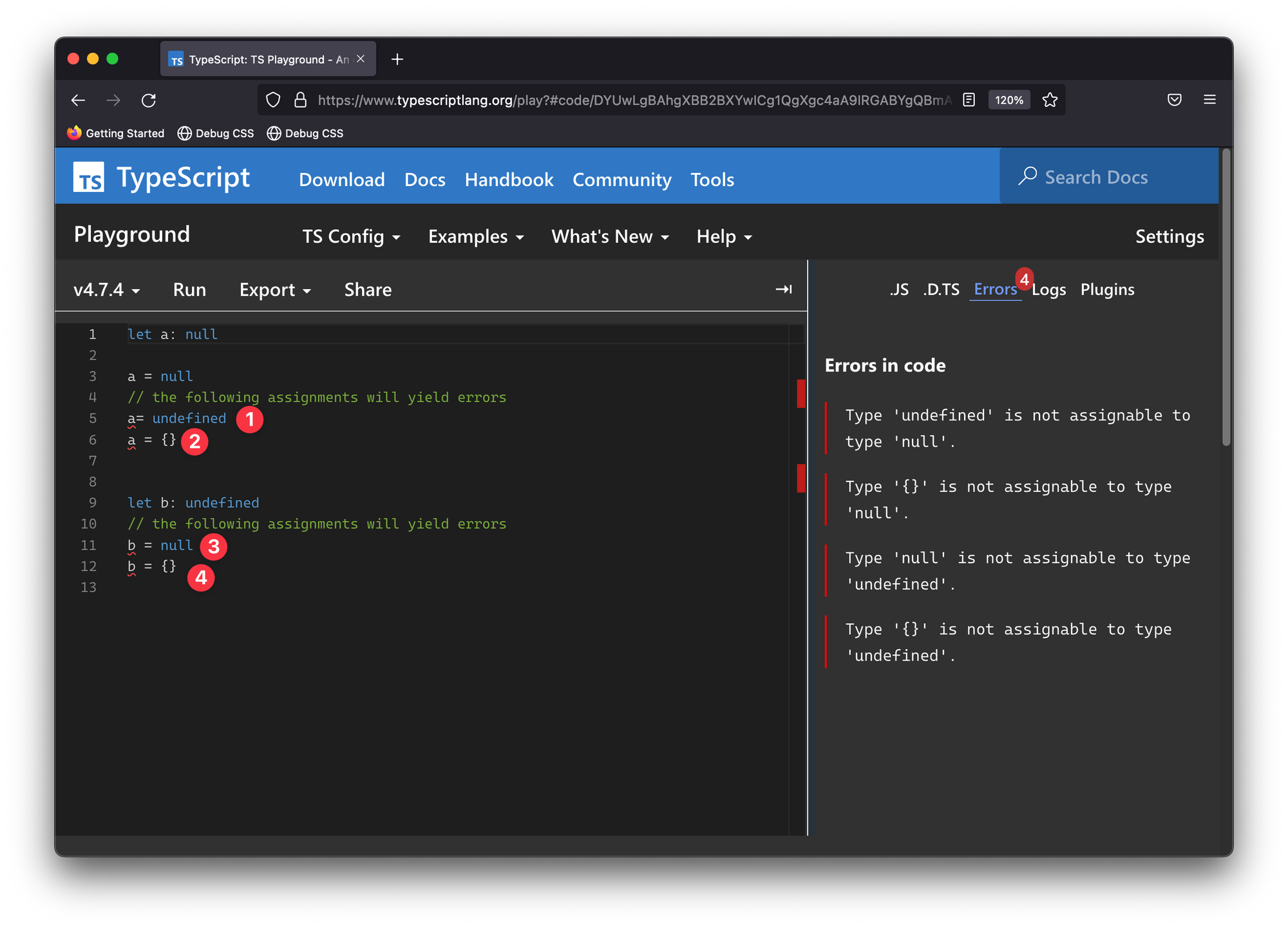

null and undefined are equally valid types, e.g., consider the following:

// explicit null

let a: null

a = null

// the following assignments will yield errors

a= undefined

a = {}

// explicit undefined

let b: undefined

// the following assignments will yield errors

b = null

b = {}

In certain cases, the Typescript compiler cannot tell whether a certain value is defined or not, i.e., not null or undefined.

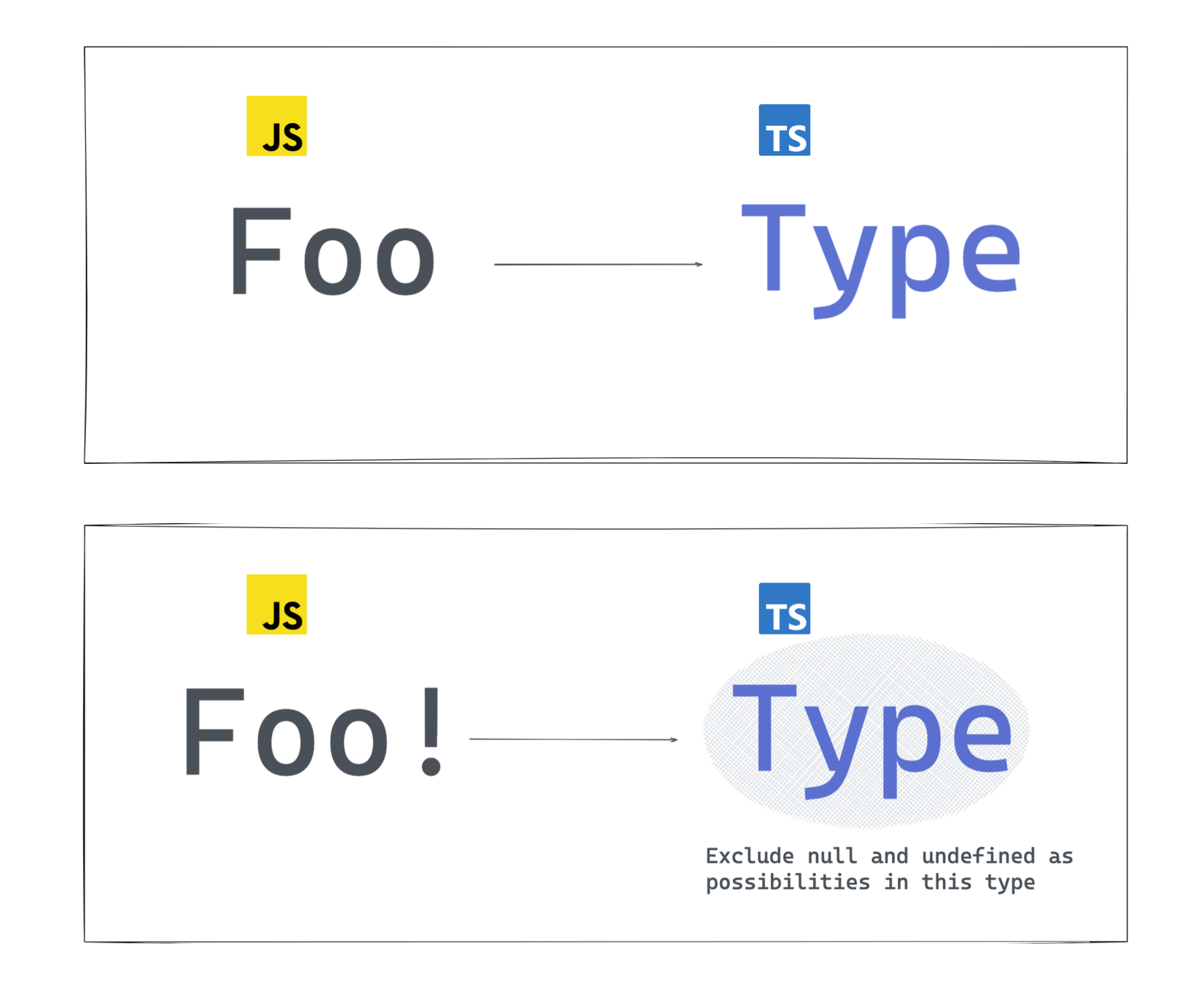

For example, assuming you had a value Foo.

Foo! produces a value of the type of Foo with null and undefined excluded.

You essentially say to the Typescript compiler, I am sure, Foo will NOT be null or undefined

Let’s explore a naive example.

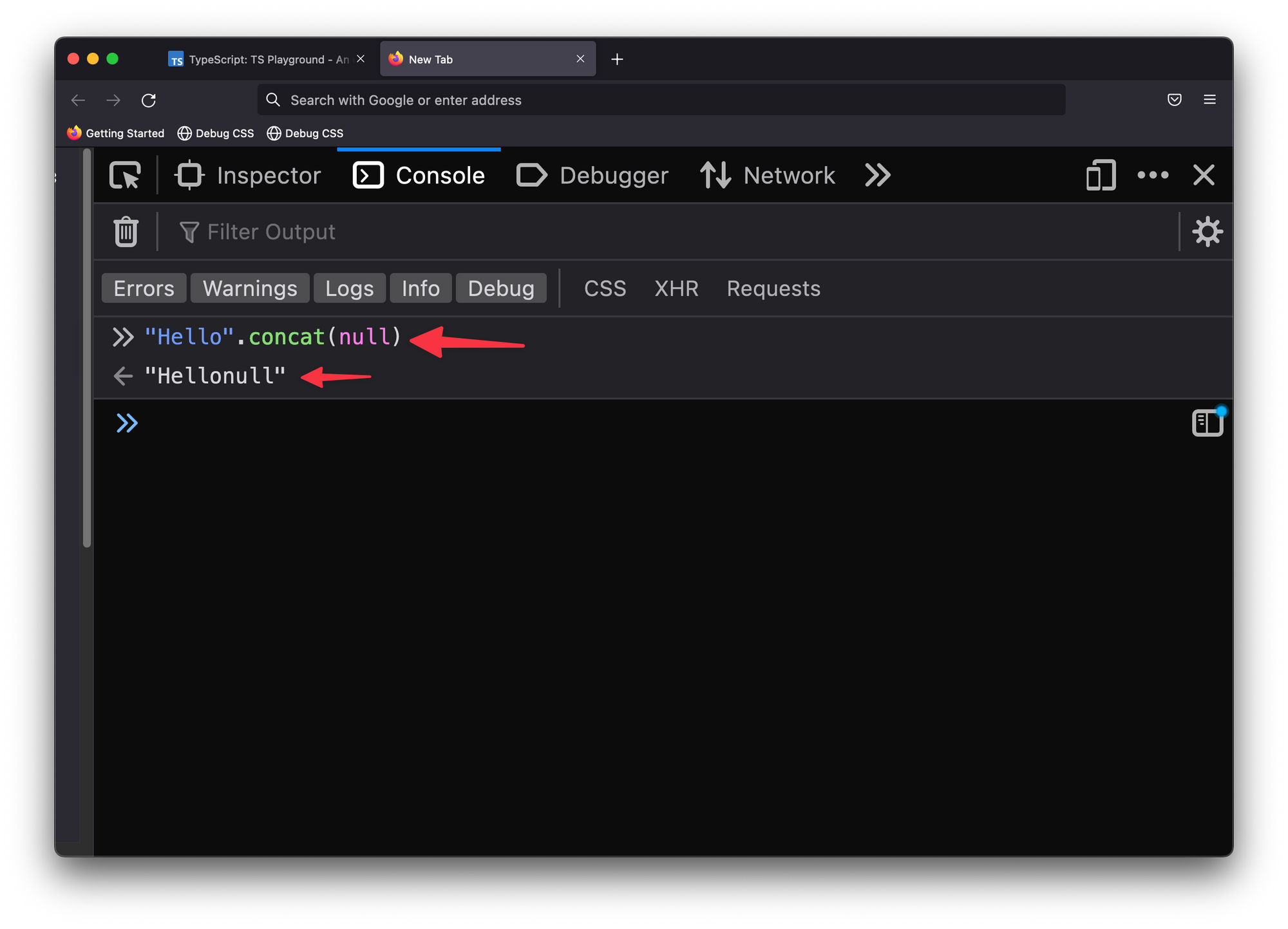

In standard Javascript, you may concatenate two strings with the .concat method:

const str1 = "Hello"

const str2 = "World"

const greeting = str1.concat(' ', str2)

// Hello World

Write a simple duplicate string function that calls .concat with itself as an argument:

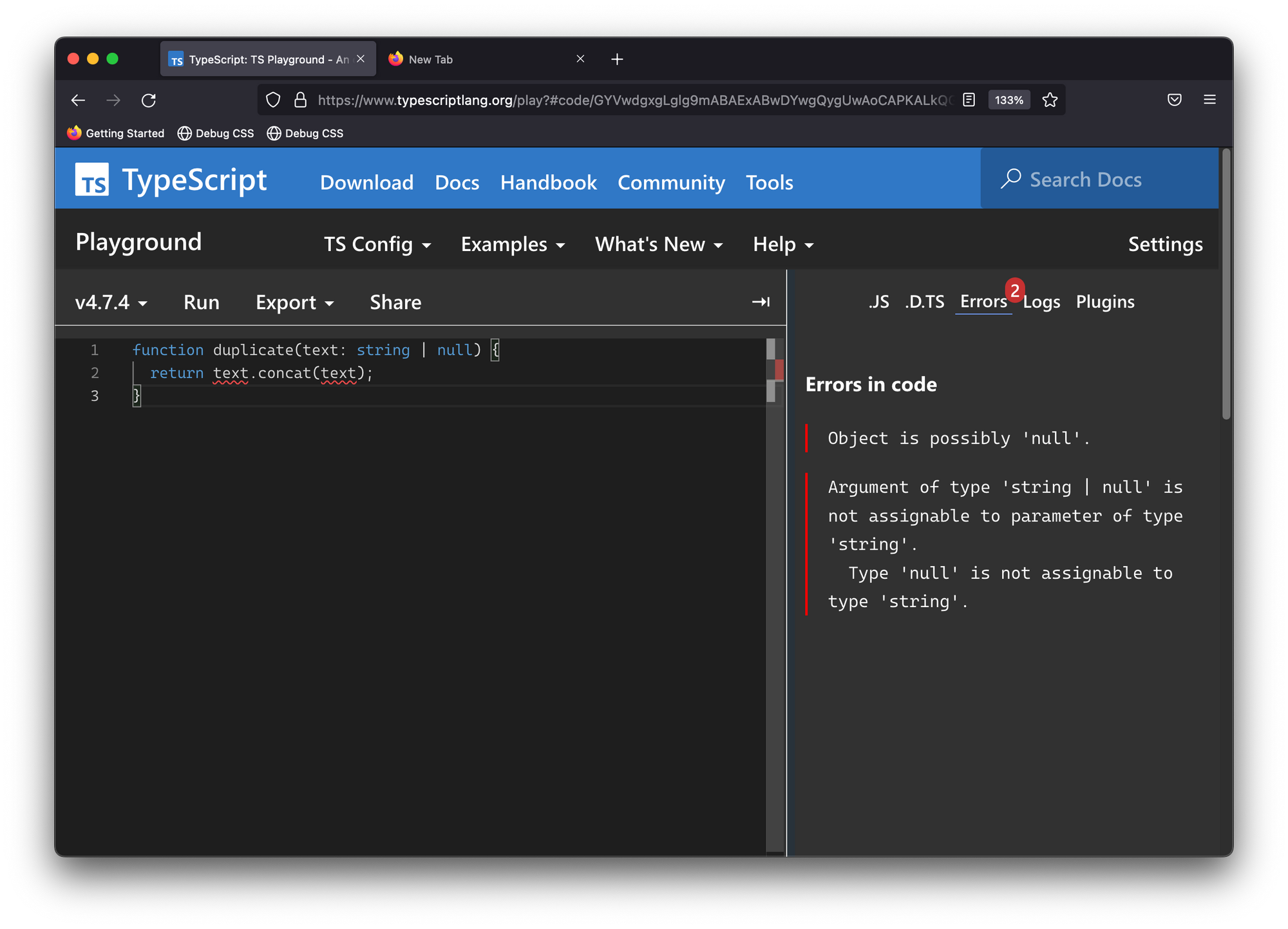

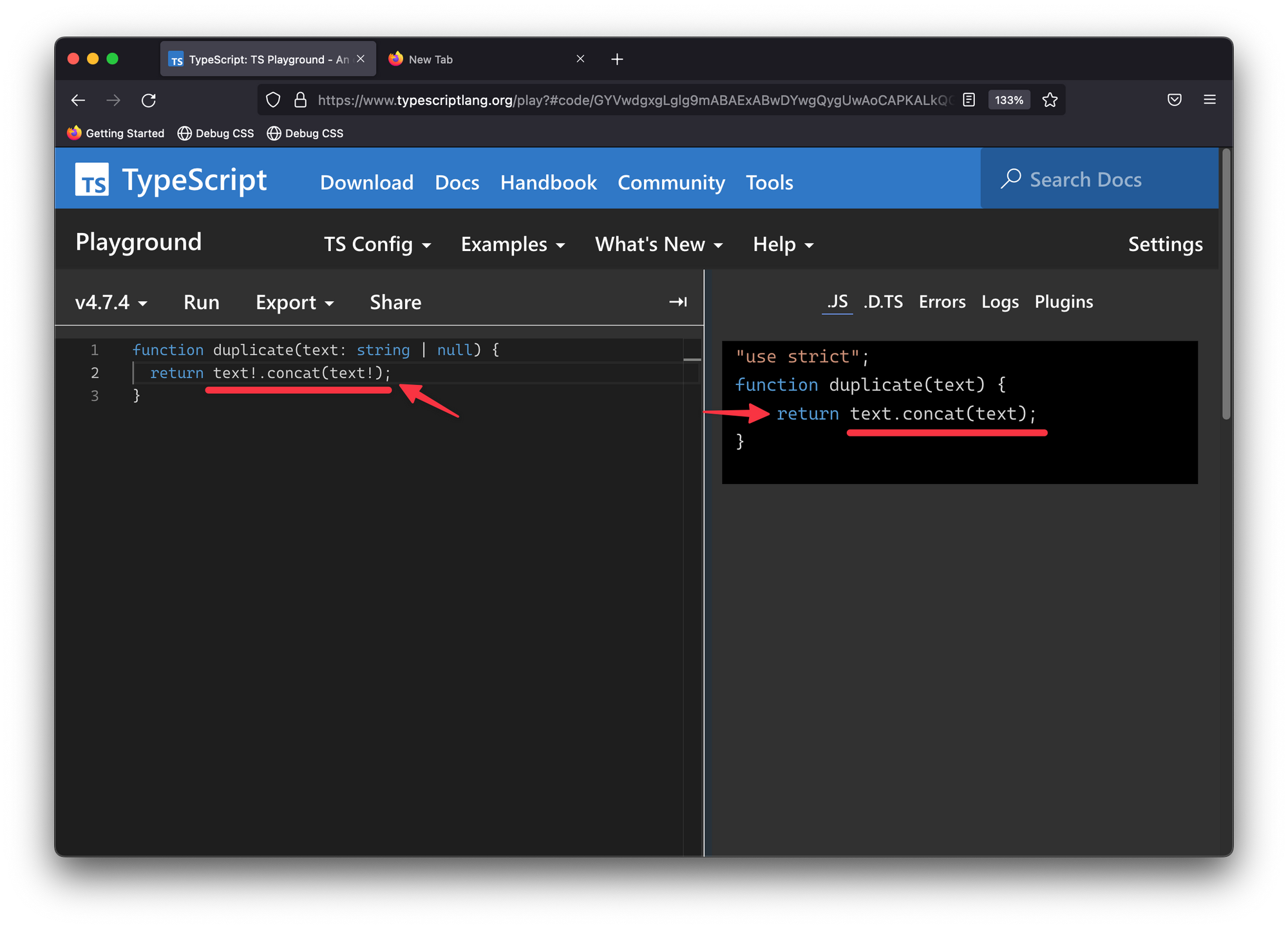

function duplicate(text: string | null) {

return text.concat(text);

}

Note that the argument text is typed as string | null

In strict mode, Typescript will complain here, as calling concat with null can lead to unexpected results.

The typescript error will read: Object is possibly 'null'.(2531)

On the flip side, a rather lazy way to silence the compiler error is to use the non-null assertion operator:

function duplicate(text: string | null) {

return text!.concat(text!);

}

Note the exclamation mark after the text variable, i.e, text!

The text type represents string | null.

text! represents just string i.e., with null or undefined removed from the variable type.

The result? You’ve silenced the Typescript error.

However, this is a silly fix.

duplicate can indeed be called with null, which may lead to unexpected results.

Note that the following example also holds true if text is an optional property:

// text could be "undefined"

function duplicate(text?: string) {

return text!.concat(text!);

}

Pitfalls (and what to do)

When working with Typescript as a new user, you may feel like you’re fighting a lost battle.

The errors don’t make sense to you.

Your goal is to remove the error and move on with your life as swiftly as you can.

However, you should be careful with using the non-null assertion operator.

Silencing a Typescript error doesn’t mean there may not still be an underlying issue—if unaddressed.

As you saw in the earlier example, you lose every relevant Typescript safety against wrong usages where null and undefined could be unwanted.

So, what should you do?

If you write React, consider an example you’re likely familiar with:

const MyComponent = () => {

const ref = React.createRef<HTMLInputElement>();

//compilation error: ref.current is possibly null

const goToInput = () => ref.current.scrollIntoView();

return (

<div>

<input ref={ref}/>

<button onClick={goToInput}>Go to Input</button>

</div>

);

};

In the example above (for those who do not write React), in the React mental model, ref.current will certainly be available at the time the button is clicked by the user.

The ref object is set soon after the UI elements are rendered.

Typescript does not know this, and you may be forced to use the non-null assertion operator here.

Essentially, say to the Typescript compiler, I know what I’m doing, you don’t.

const goToInput = () => ref.current!.scrollIntoView();

Note the exclamation mark !.

This “fixes” the error.

However, if in the future, someone removes the ref from the input, and there were no automated tests to catch this, you now have a bug.

// before

<input ref={ref}/>

// after

<input />

Typescript will be unable to spot the error in the following line:

const goToInput = () => ref.current!.scrollIntoView();

By using the non-null assertion operator, the Typescript compiler will act as if null and undefined are never possible for the value in question. In this case, ref.current.

Solution 1: find an alternative fix

The first line of action you should employ is to find an alternative fix.

For example, often you can explicitly check for null and undefined values.

// before

const goToInput = () => ref.current!.scrollIntoView();

// now

const goToInput = () => {

if (ref.current) {

//Typescript will understand that ref.current is certianly

//avaialble in this branch

ref.current.scrollIntoView()

}

};

// alternatively (use the logical AND operator)

const goToInput = () => ref.current && ref.current.scrollIntoView();

Numerous engineers will argue over the fact that this is more verbose.

That’s correct.

However, choose verbose over possibly breaking code being pushed to production.

This is a personal preference. Your mileage may differ.

Solution 2: explicitly throw an error

In cases where an alternative fix doesn’t cut it and non-null assertion operator seems like the only solution, I typically advise you throw an error before doing this.

Here’s an example (in pseudocode):

function doSomething (value) {

// for some reason TS thinks value could be

// null or undefined but you disagree

if(!value) {

// explicilty assert this is the case

// throw an error or log this somewhere you can trace

throw new Error('uexpected error: value not present')

}

// go ahead and use the non-null assertion operator

console.log(value)

}

A practical case where I’ve found myself sometimes doing this is while using Formik.

Except things have changed, I do think Formik is poorly typed in numerous instances.

The example may go similar to you've done your Formik validation and are sure that your values exist.

Here’s some pseudocode:

<Formik

validationSchema={...}

onSubmit={(values) => {

// you are sure values.name should exist because you had

// validated in validationSchema but Typescript doesn't know this

if(!values.name) {

throw new Error('Invalid form, name is required')

}

console.log(values.name!)

}}>

</Formik>

In the pseudocode above, values could be typed as:

type Values = {

name?: string

}

But before you hit onSubmit, you’ve added some validation to show a UI form error for the user to input a name before moving on to the form submission.

There are other ways to get around this, but if you find yourself in such a case where you’re sure a value exists but can’t quite communicate that to the Typescript compiler, use the non-null assertion operator. But also add an assertion of your own by throwing an error you can trace.

How about an implicit assertion?

Even though the name of the operator reads non-null assertion operator, no “assertion” is actually being made.

You’re mostly asserting (as the developer), that the value exists.

The Typescript compiler does NOT assert that this value exists.

So, if you must, you may go ahead and add your assertion, e.g., as discussed in the earlier section.

Also, note that no more Javascript code is emitted by using the non-null assertion operator.

As stated earlier, there’s no assertion done here by Typescript.

Consequently, Typescript will not emit some code that checks if this value exists or not.

The Javascript code emitted will act as if this value always existed.

Conclusion

TypeScript 2.0 saw the release of the non-null assertion operator. Yes, it’s been around for some time (released in 2016). At the time of writing, the latest version of Typescript is v4.7.

If the typescript compiler complains about a value being null or undefined, you can use the ! operator to assert that the said value is not null or undefined.

Only do this if you’re certain that is the case.

Even better, go ahead and add an assertion of your own, or try to find an alternative solution.

Some may argue that if you need to use the non-null assertion operator every time, it’s a sign you’re poorly representing the state of your application state via Typescript.

I agree with this school of thought.

3: What is a “.d.ts” file in TypeScript?

TLDR

.d.ts files are called type declaration files. They exist for one purpose only: to describe the shape of an existing module and they only contain type information used for type checking.

Introduction

Upon learning the basics of TypeScript, you unlock superpowers.

At least that’s how I felt.

You automagically get warnings on potential errors, you get auto-completion out of the box in your code editor.

While seemingly magical, nothing with computers are.

So, what’s the trick here, TypeScript?

In a clearer language, how does TypeScript know so much? How does it decide what API is correct or not? What methods are available on a certain object or class, and which aren’t?

The answer is less magical.

TypeScript relies on types.

Occasionally, you do not write these types, but they exist.

They exist in files called declaration files.

These are files with a .d.ts ending.

A simple example

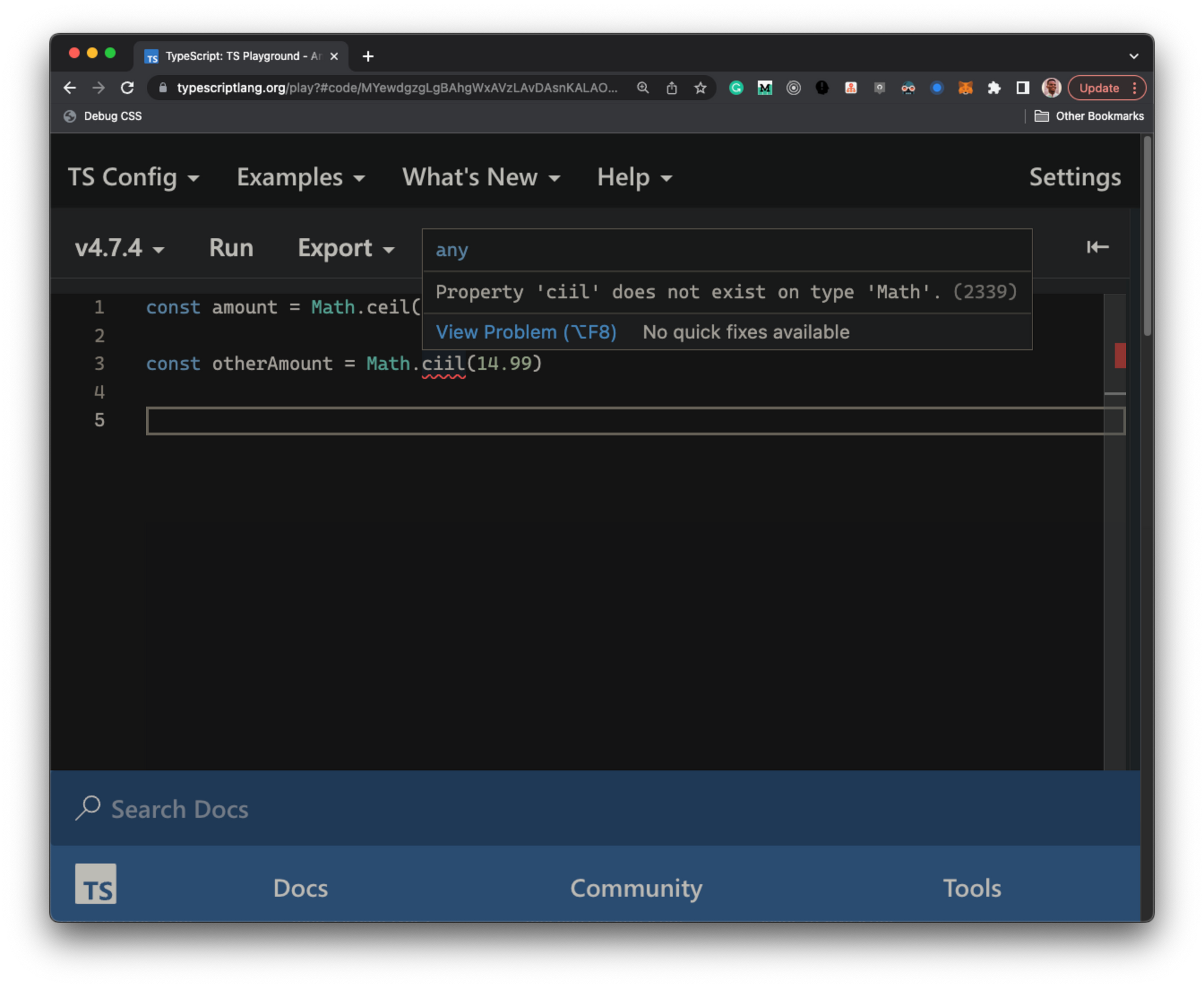

Consider the following TypeScript code:

// valid

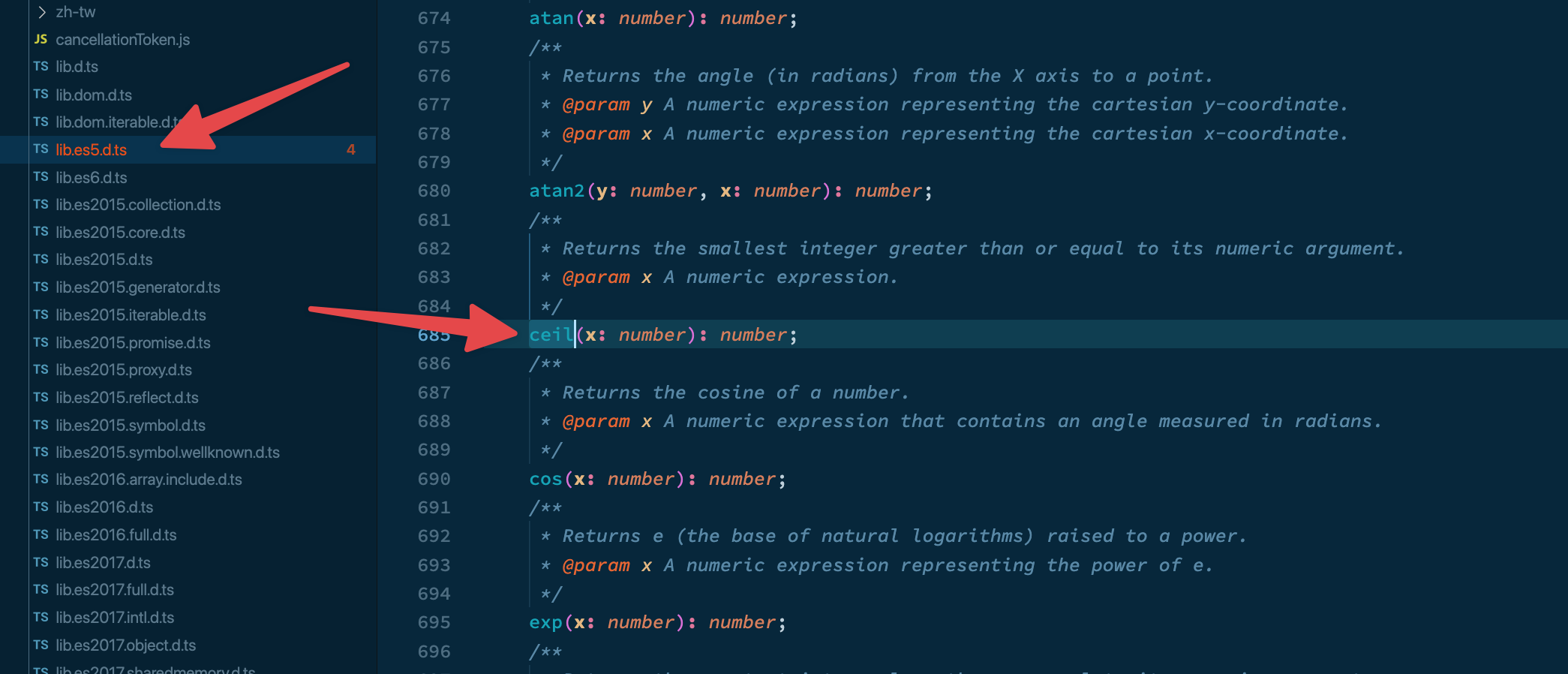

const amount = Math.ceil(14.99)

// error: Property 'ciil' does not exist on type 'Math'.(2339)

const otherAmount = Math.ciil(14.99)

The first line of code is perfectly valid, but the second, not quite.

And TypeScript is quick to spot the error: Property 'ciil' does not exist on type 'Math'.(2339)

How did TypeScript know ciil does not exist on the Math object?

The Math object isn’t a part of our implementation. It’s a standard built-in object.

So, how did TypeScript figure that out?

The answer is there are declaration files that describe these built-in objects.

Think of a declaration file as containing all type information relating to a certain module. It contains no actual implementation, just type information.

These files have a .d.ts ending.

Your implementation files will either have .ts or .js endings to represent TypeScript or javascript files.

These declaration files have no implementations. They only contain type information and have a .d.ts file ending.

Built-in Type Definitions

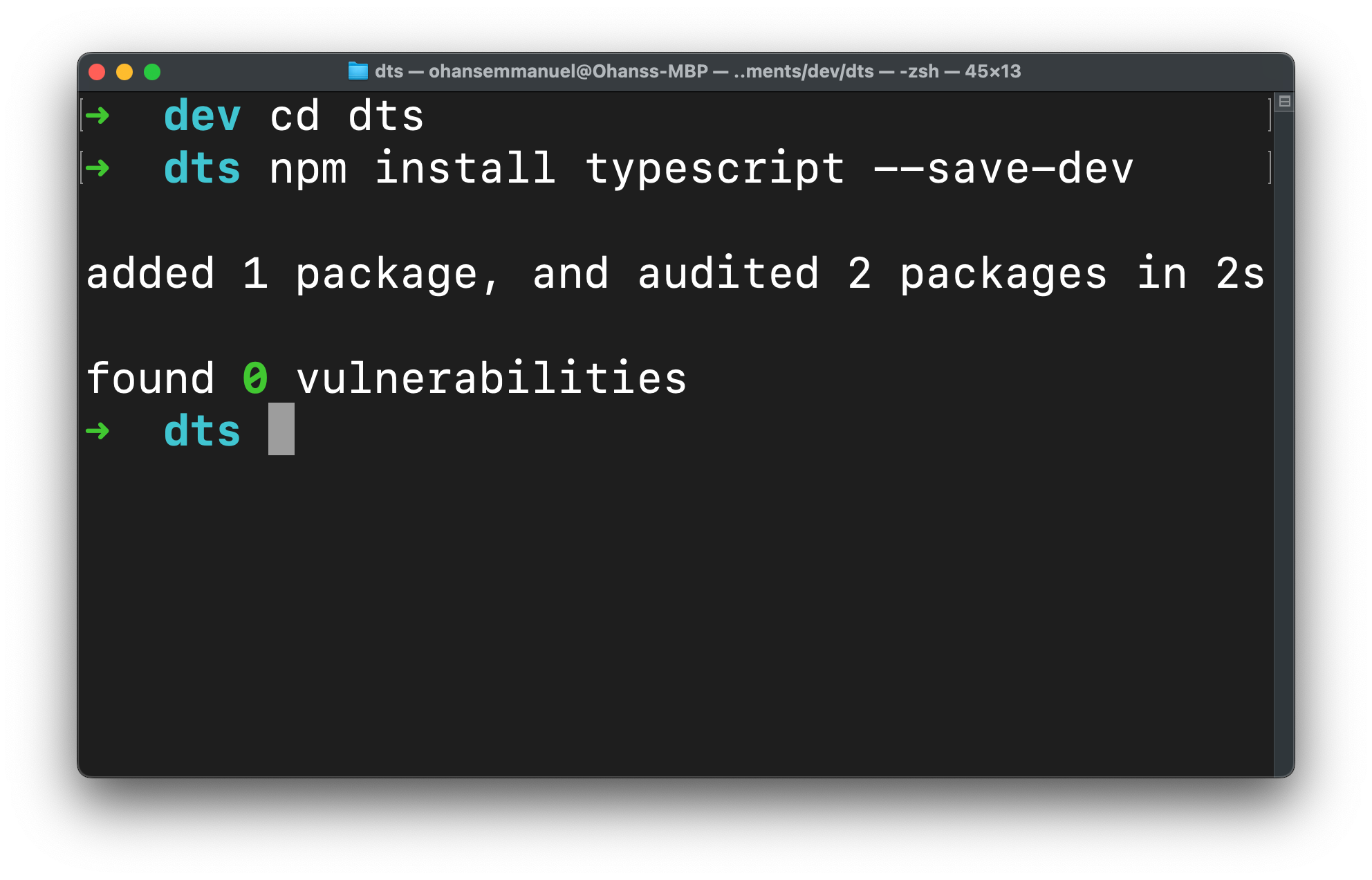

A great way to understand this in practice is to set up a brand-new TypeScript project and explore the type definition files for top-level objects like Math.

Let’s do this.

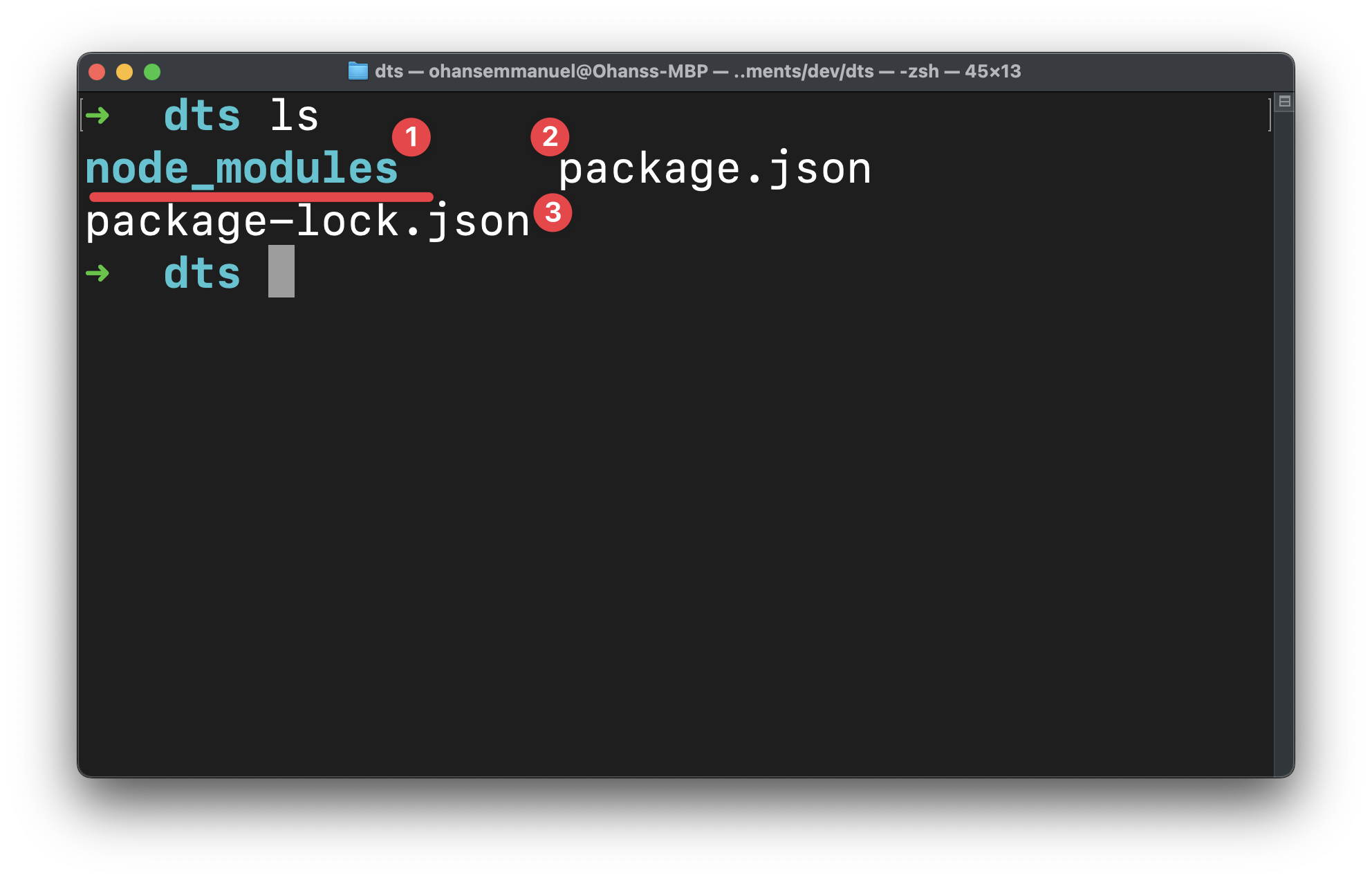

Create a new directory, and name it whatever’s appropriate.

I’ll call mine dts.

Change directories to this newly created folder:

cd dts

Now initialise a new project:

npm init --yes

Install TypeScript:

npm install TypeScript --save-dev

This directory should contain 2 files and one subdirectory

Open the folder in your favourite code editor.

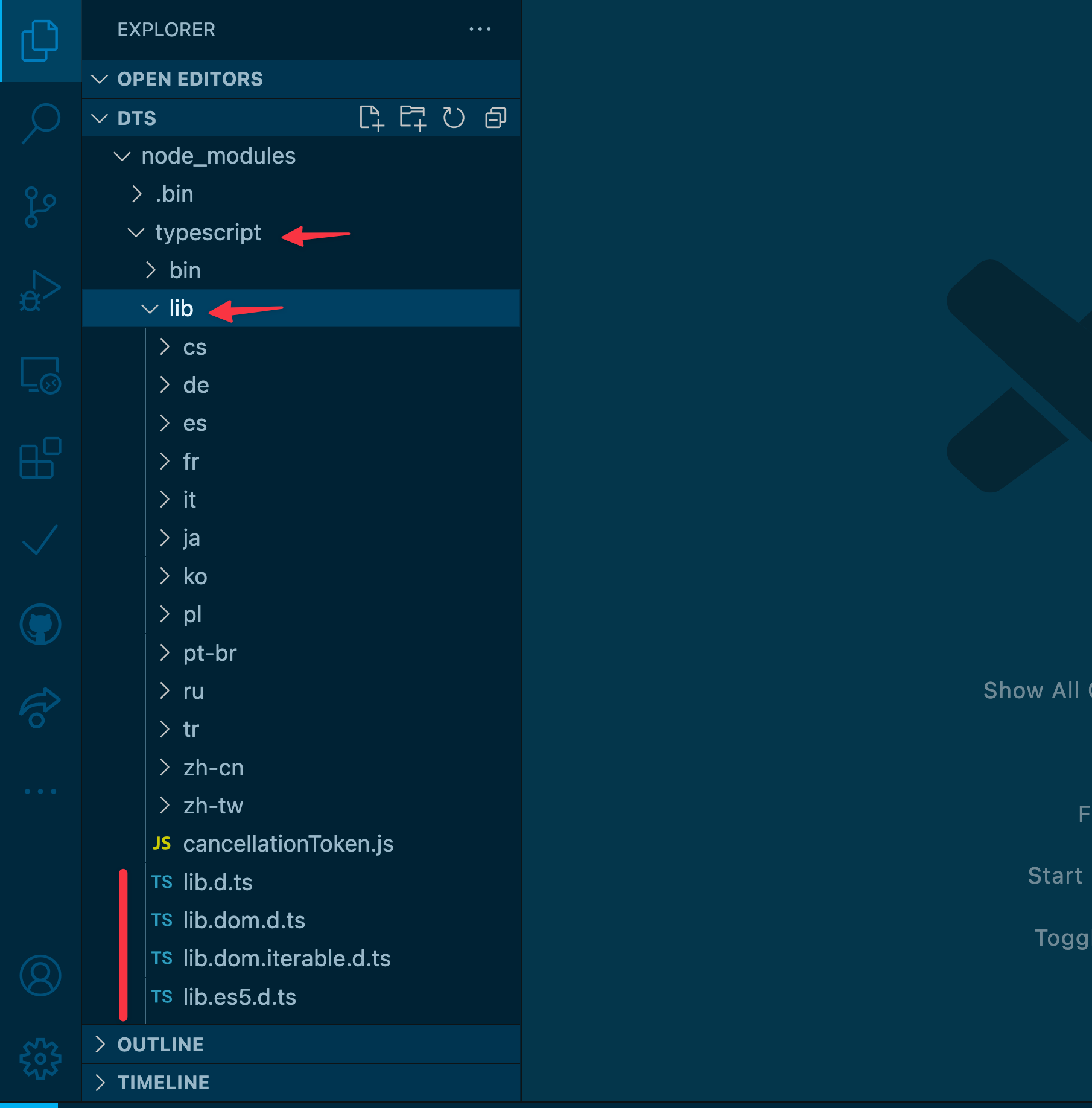

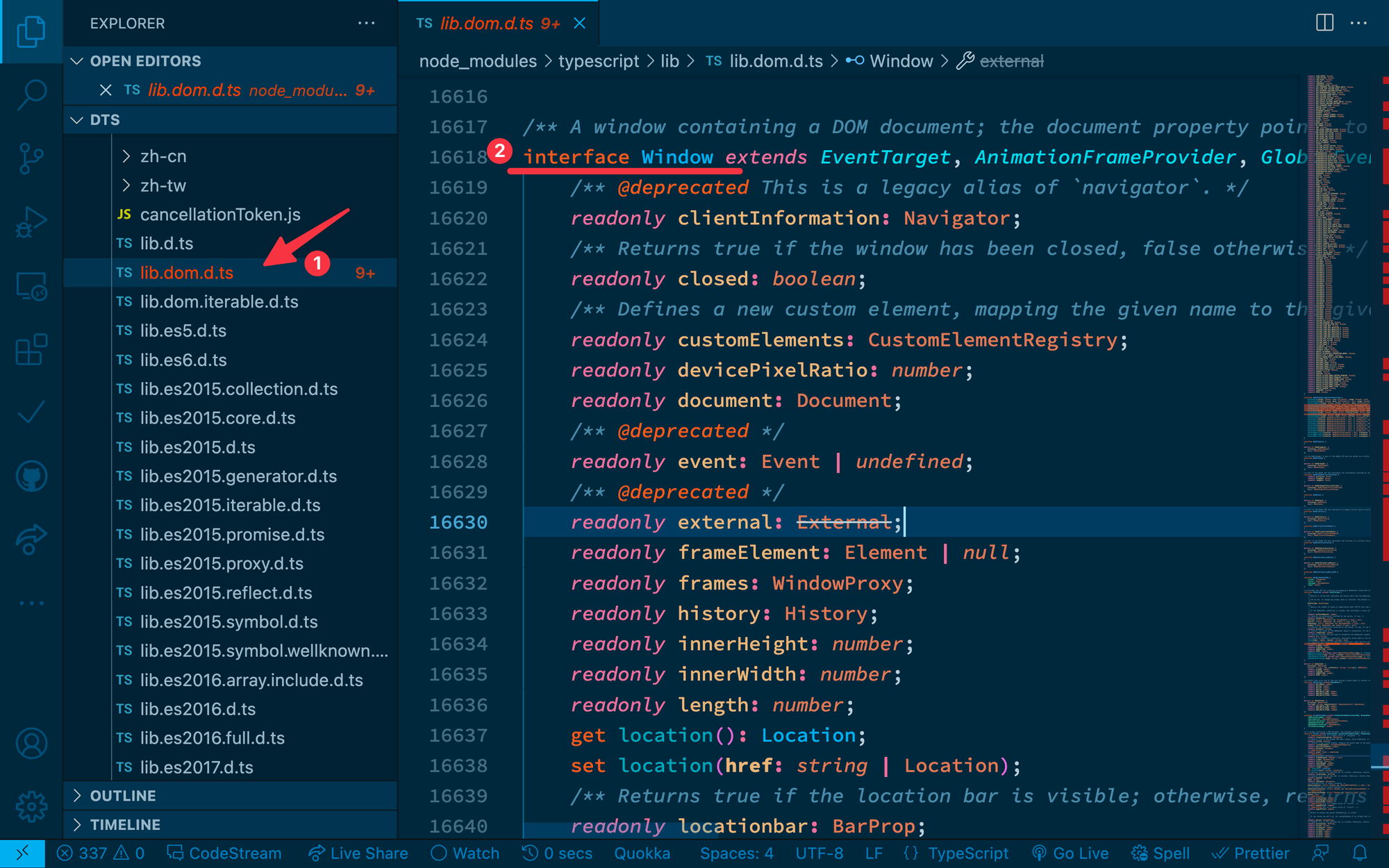

If you investigate the TypeScript directory within node_modules, you’ll find a bunch of type declaration files out of the box.

These are present courtesy of installing TypeScript.

By default, TypeScript will include type definition for all DOM APIs, e.g., think window and document.

As you inspect these type declaration files, you’ll notice that the naming convention is straightforward.

It follows the pattern: lib.[something].d.ts.

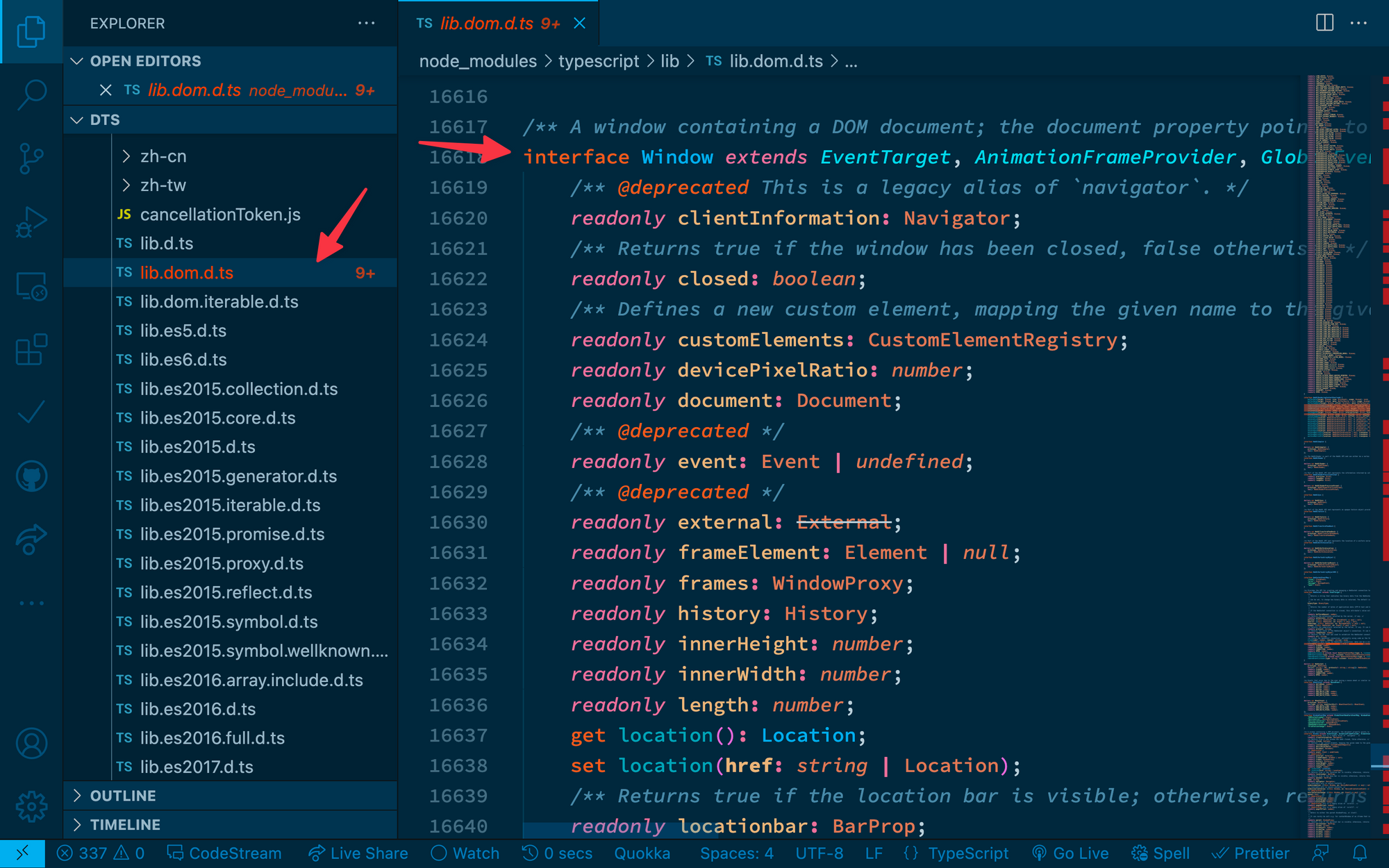

Open up the lib.dom.d.ts declaration file to view all declarations related to the browser DOM API.

As you can see, this is quite a gigantic file.

But so are all the APIs available in the DOM.

Awesome!

Now, if you take a look at the lib.es5.d.ts file, you’ll see the declaration for the Math object, containing the ceil property.

Next time you think, wow, TypeScript is wonderful. Remember, a big part of that awesomeness is due to the lesser-known heroes: type declaration files.

It’s not magic. Just type declaration files.

External type definitions

What about APIs that aren’t built-in?

There’s a host of npm packages out there to do just about anything you want.

Is there a way for TypeScript to also understand the relevant type relationships for the said module?

Well, the answer is a resounding yes.

There are typically two ways a library author may do this.

(1) Bundled Types

In this case, the author of the library has already bundled the type declaration files as part of the package distribution.

You typically don’t need to do anything.

You just go ahead and install the library in your project, you import the required module from the library and see if TypeScript should automatically resolve the types for you.

Remember, this is not magic.

The library author has bundled the type declaration file in the package distribution.

(2) DefinitelyTyped (@types)

Imagine a central public repository that hosts declaration files for thousands of libraries?

Well, bring that image home.

This repository already exists.

The DefinitelyTyped repository is a centralised repository that stores the declaration files for thousands of libraries.

In all honestly, the vast majority of commonly used libraries have declaration files available on DefinitelyTyped.

These type definition files are automatically published to npm under the @types scope.

For example, if you wanted to install the types for the react npm package, you’d do this:

npm install --save-dev @types/react

If you find yourself using a module whose types TypeScript does not automatically resolve, attempt installing the types directly from DefinitelyTyped.

See if the types exist there. e.g.:

npm install --save-dev @types/your-library

Definition files added in this manner will be saved to node_modules/@types.

TypeScript will automatically find these. So, there’s no additional step for you to take.

Writing your declaration files

In the uncommon event that a library didn’t bundle its types and does not have a type definition file on DefinitelyTyped, you can write your own declaration files.

Writing declaration files in-depth is beyond the scope of this article, but a use case you’ll likely come across is silencing errors about a particular module without a declaration file.

Declaration files all have a .d.ts ending.

So to create yours, create a file with a .d.ts ending.

For example, assuming I have installed library untyped-module in my project.

untyped-module has no referenced type definition files, so TypeScript complains about this in my project.

To silence this warning, I may create a new untyped-module.d.ts file in my project with the following content:

declare module "some-untyped-module";

This will declare the module as type any.

We won’t get any TypeScript support for that module, but you’d have silenced the TypeScript warning.

Ideal next steps would include opening an issue in the module’s public repository to include a TypeScript declaration file, or writing out a decent one yourself.

Conclusion

Next time you think, wow, TypeScript is remarkable. Remember, a big part of that awesomeness is due to the lesser-known heroes: type declaration files.

Now you understand how they work!

4: How Do You Explicitly Set a New Property on ‘window’ in Typescript?

TLDR

Extend the existing interface declaration for the Window object.

Introduction

Knowledge builds upon knowledge.

Whoever said that was right.

In this section, we will build upon the knowledge from the last two sections:

Interfaces vs Types in Typescript

What is a d.t.s file in Typescript

Ready?

First, I must say, in my early days with Typescript, this was a question I googled over and over again.

I never got it. And I didn’t bother, I just googled.

That’s never the right mentality to gaining mastery over a subject.

Let’s discuss the solutions to this.

Understanding the problem

The problem here is actually straightforward to reason about.

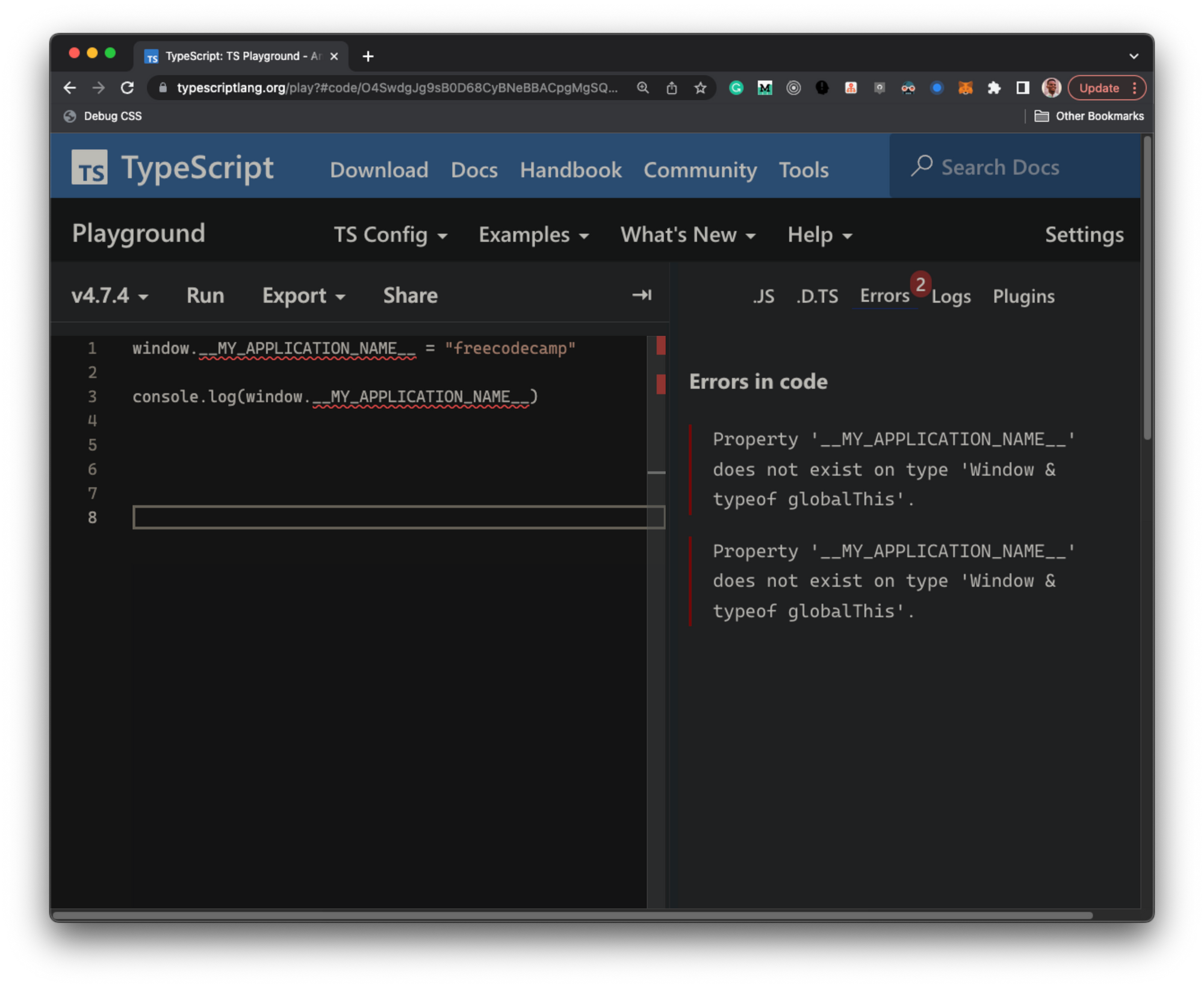

Consider the following Typescript code:

window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ = "freecodecamp"

console.log(window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__)

Typescript is quick to let you know __MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ does not exist on type ‘Window & typeof globalThis’.

Okay, Typescript.

We get it.

On closer look, remember from the last section on declaration files that there’s a declaration file for all existing browser APIs. This includes built-in objects such as window.

If you look in the lib.dom.d.ts declaration file, you’ll find the Window interface described.

In layman’s terms, the error here says the Window interface describes how I understand the window object and its usage. That interface does not specify a certain __MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ property.

Fixing the error

In the Types vs interface section, I explained how to extend an interface.

Let’s apply that knowledge here.

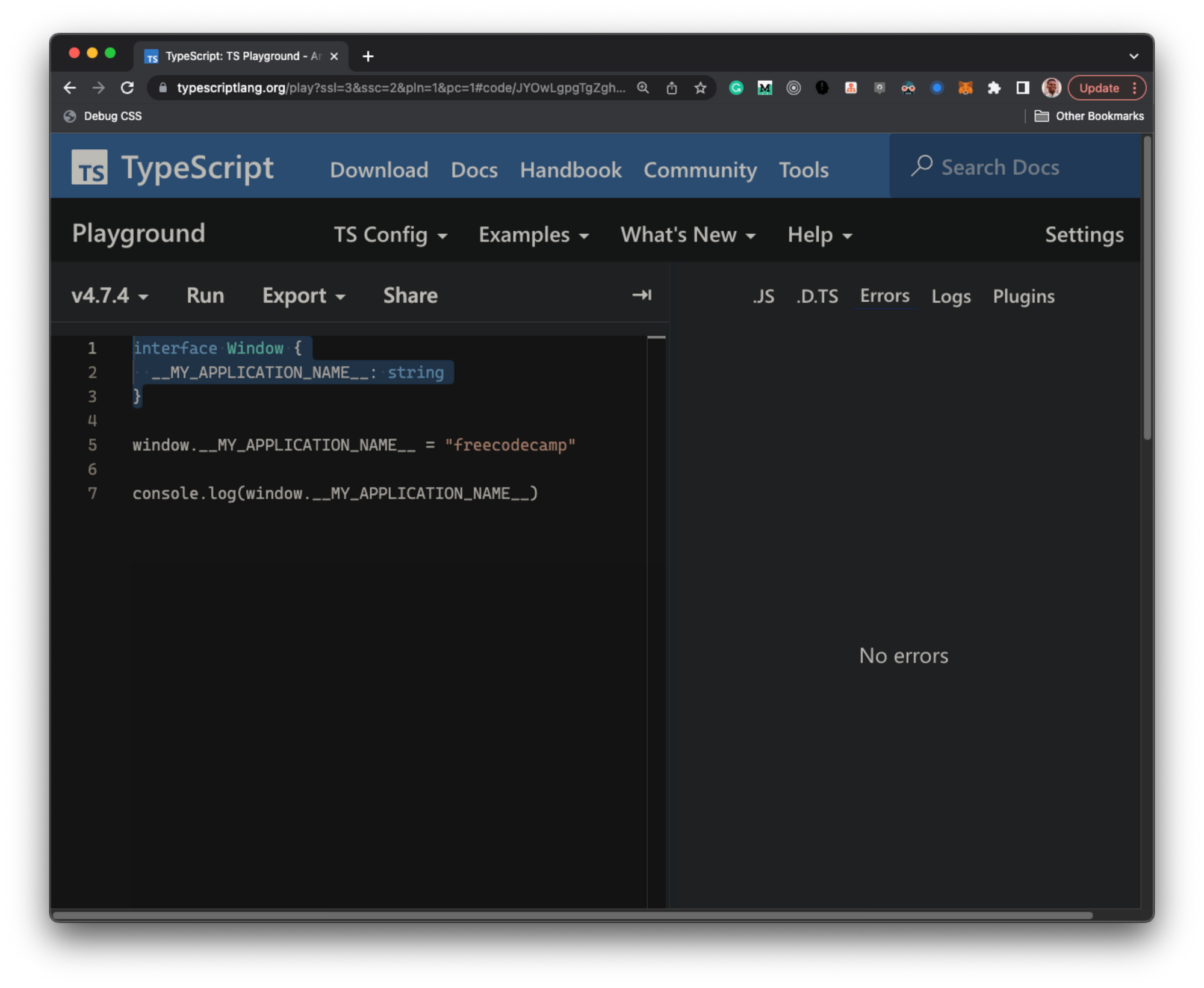

We can extend the Window interface declaration to become aware of the __MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ property.

Here’s how:

// before

window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ = "freecodecamp"

console.log(window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__)

// now

interface Window {

__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__: string

}

window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ = "freecodecamp"

console.log(window.__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__)

Errors banished!

Remember that a key difference between types and interfaces is that interfaces can be extended by declaring it multiple times.

What we’ve done here is declared the Window interface one more time, hence extending the interface declaration.

A real-world solution

I’ve solved this problem within the Typescript playground to show you the solution in its simplest form, i.e., the crux.

In the real world, though, you wouldn’t extend the interface within your code.

So, what should you do instead?

Give it a guess, perhaps?

Yes, you were close … or perhaps right!

Create a type definition file!

For example, create a window.d.ts file with the following content:

interface Window {

__MY_APPLICATION_NAME__: string

}

And there you go.

You’ve successfully extended the Window interface and solved the problem.

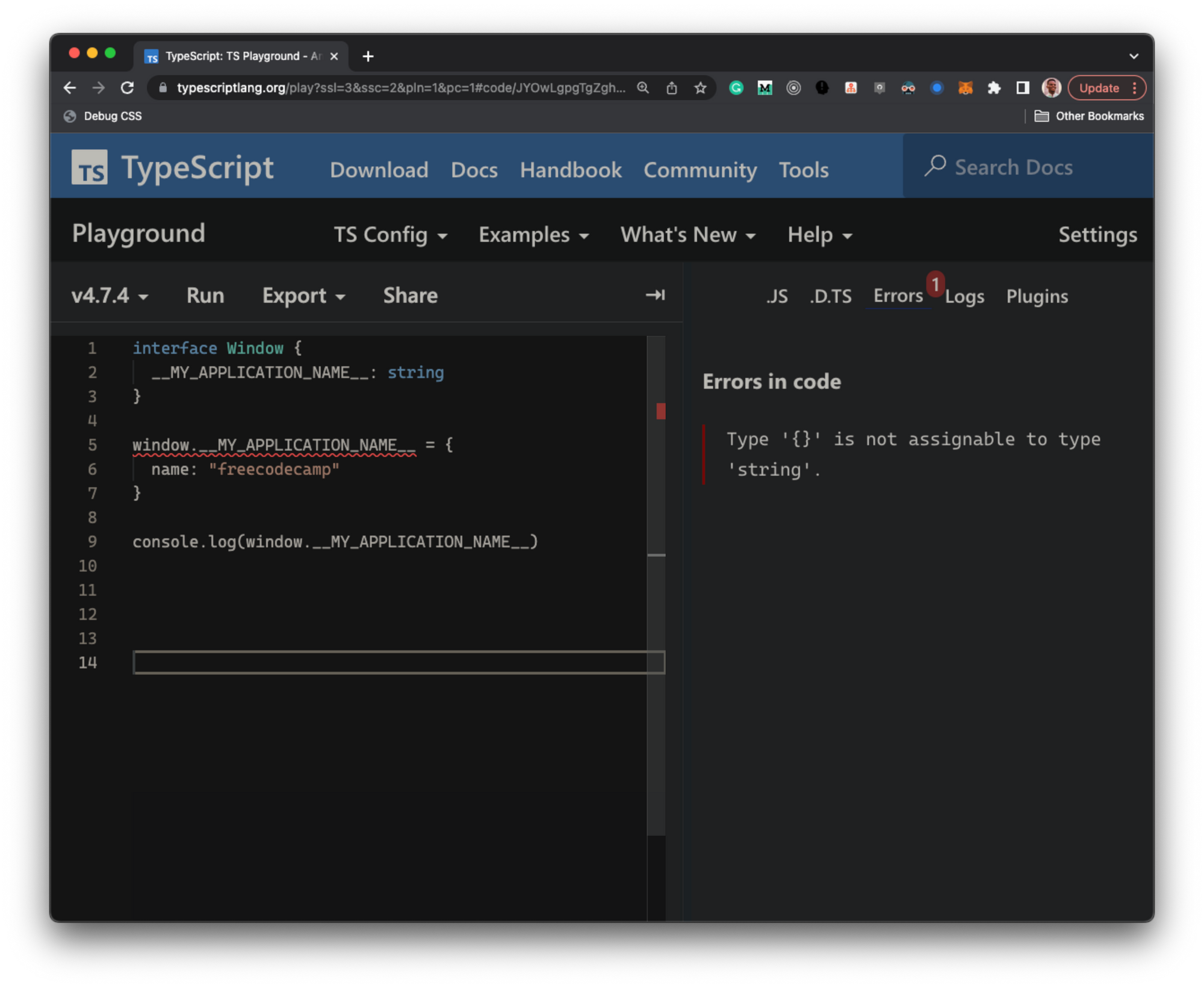

If you went ahead to assign the wrong value type to the __MY_APPLICATION_NAME__ property, you now have strong type checking enabled.

Voilà.

Conclusion

In older stack overflow posts, you’ll find more complicated answers based on older Typescript versions.

The solution is easier to reason about in modern Typescript.

Now you know 😉

5: Are Strongly Typed Functions as Parameters Possible in Typescript?

TLDR

This question does not need to be overly explained. The short answer is yes.

Functions can be strongly typed — even as parameters to other functions.

Introduction

I must say, unlike other sections of this article, I never really found myself searching for this in my early Typescript days.

However, that’s not what’s most important.

It is a well-searched question, so let’s answer it!

How to use strongly typed function parameters

The accepted answer on this stack overflow post is correct — to a degree.

Assuming you had a function: speak:

function speak(callback) {

const sentence = "Hello world"

alert(callback(sentence))

}

It receives a callback that’s internally invoked with a string.

To type this, go ahead and represent the callback with a function type alias:

type Callback = (value: string) => void

And type the speak function as follows:

function speak(callback: Callback) {

const sentence = "Hello world"

alert(callback(sentence))

}

Alternatively, you could also keep the type inline:

function speak(callback: (value: string) => void) {

const sentence = "Hello world"

alert(callback(sentence))

}

And there it is!

You’ve used a strongly typed function as a parameter.

Handling functions with no return value

The accepted answer in the referenced stack overflow post for example says the callback parameter's type must be "function that accepts a number and returns type any"

That’s partly true, but the return type does NOT have to be any

In fact, do NOT use any.

If your function returns a value, go ahead and type it appropriately:

// Callback returns an object

type Callback = (value: string) => { result: string }

If your callback returns nothing, use void not any:

// Callback returns nothing

type Callback = (value: string) => void

Note that the signature of your function type should be:

(arg1: Arg1type, arg2: Arg2type) => ReturnType

Where Arg1type represents the type of the argument arg1, Arg2type the type of the arg2 argument, and ReturnType the return type of your function.

Conclusion

Functions are the primary means of passing data around in Javascript.

Typescript not only allows you to specify the input and output of functions, but you can also type functions as arguments to other functions.

Go ahead and use them with confidence.

6: How to Fix Could Not Find Declaration File for Module …?

This is a common source of frustration for Typescript beginners.

However, do you know how to fix this?

Yes, you do!

The solution to this was equally explained in the what is d.ts section.

TLDR

Create a declaration file, e.g., untyped-module.d.ts with the following content: declare module "some-untyped-module";. Note that this will explicitly type the module as any.

The solution explained

You can give the writing your declaration files section a fresh read if you don’t remember how to fix this.

Essentially, you have this error because the library in question didn’t bundle its types and does not have a type definition file on DefinitelyTyped.

This leaves you with one solution: write your own declaration file.

For example, If you have installed the library untyped-module in your project,

untyped-module has no referenced type definition files, so Typescript complains.

To silence this warning, create a new untyped-module.d.ts file in my project with the following content:

declare module "some-untyped-module";

This will declare the module as type any.

You won’t get any Typescript support for that module, but you’d have silenced the Typescript warning.

Ideal next steps would include opening an issue in the module’s public repository to include a Typescript declaration file or writing out a decent one yourself (beyond the scope of this article).

7: How Do I Dynamically Assign Properties to an Object in Typescript?

TLDR

If you cannot define the variable type at declaration time, use the Record utility type or an object index signature.

Introduction

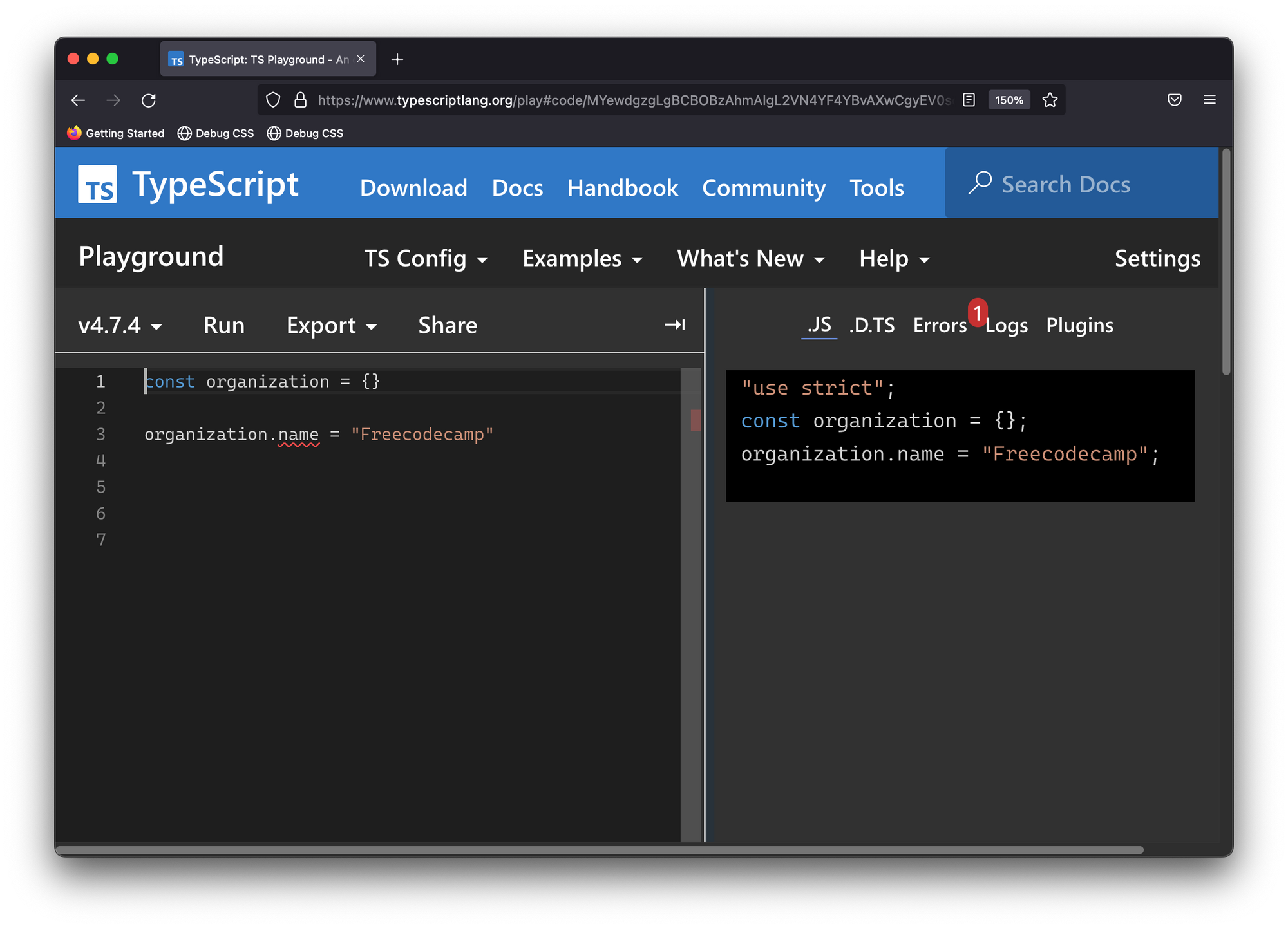

Consider the following example:

const organization = {}

organization.name = "Freecodecamp"

This seemingly harmless piece of code throws a Typescript error on dynamically assigning name to the organization object.

The source of confusion, and perhaps rightly justified if you’re a Typescript beginner, is, how is something seemingly so simple a problem in Typescript?

Understanding the problem

Generally speaking, Typescript determines the type of a variable when it is declared, and this determined type doesn’t change, i.e., it stays the same all through your application.

There are exceptions to this rule when considering type narrowing or working with the any type, but this is a general rule to remember otherwise.

In the earlier example, the organization object is declared as follows:

const organization = {}

There is no explicit type assigned to the organization variable, so Typescript infers the type of organization based on the declaration to be {} i.e., the literal empty object.

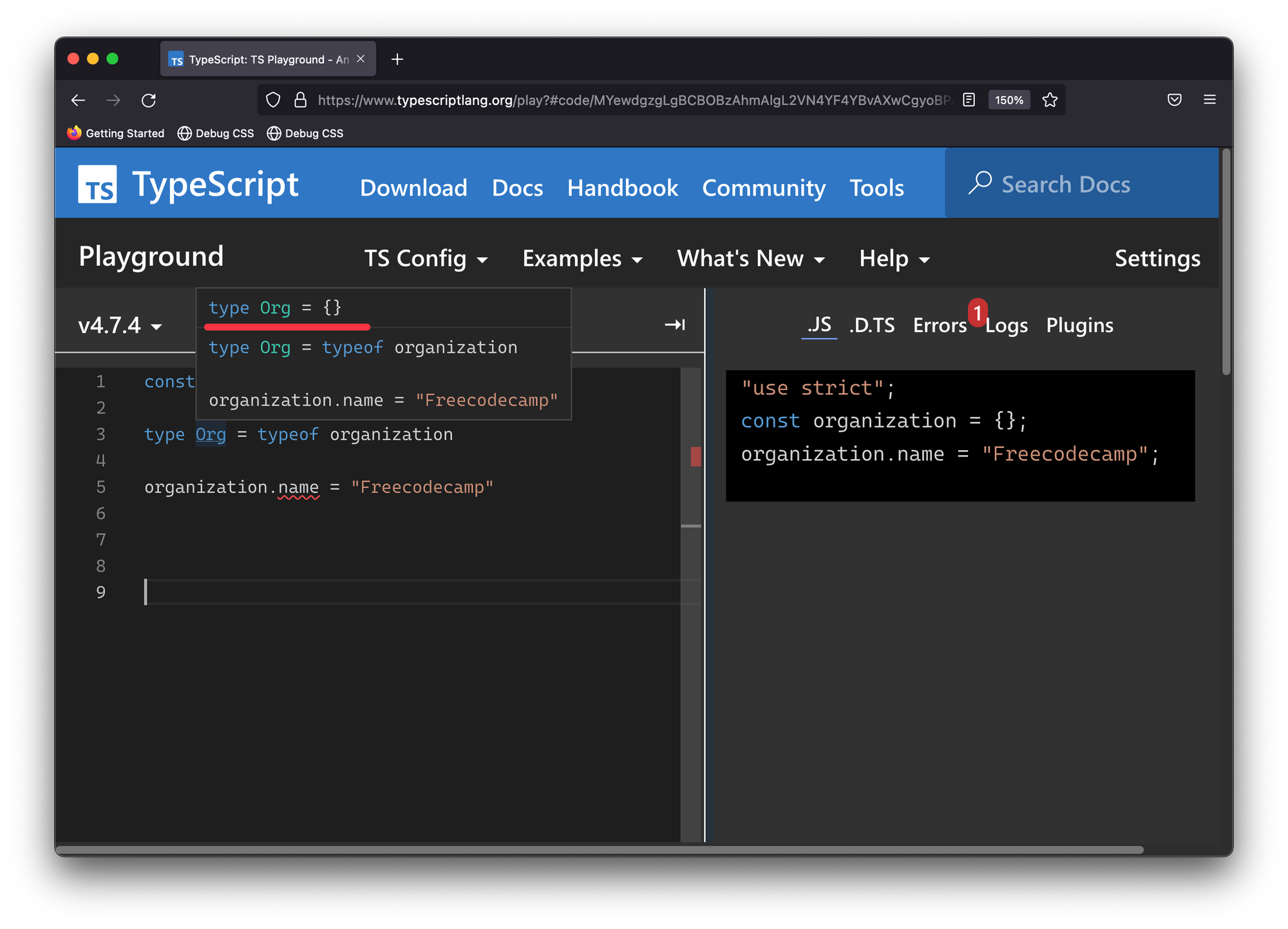

For example, if you add a type alias, you can explore the type of organization:

type Org = typeof organization

When you then try to reference the name prop on this empty object literal:

organization.name = ...

Typescript yells.

Property 'name' does not exist on type ‘ {}‘When you understand the issue, the error does seem appropriate.

Let’s fix this.

Resolving the error

There are numerous ways you can resolve the Typescript error here. Let’s consider these:

1. Explicitly type the object at declaration time

This is the easiest solution to reason about.

At the time you declare the object, go ahead and type it. Furthermore, assign it all the relevant values.

type Org = {

name: string

}

const organization: Org = {

name: "Freecodecamp"

}

This removes every surprise.

You’re clearly stating what this object type is and rightly declaring all relevant properties when you create the object.

However, this is not always feasible if the object properties must be added dynamically.

2. Use an object index signature

Occasionally, the properties of the object truly need to be added at a later time than when declared.

In this case, you can leverage the object index signature as follows:

type Org = {[key: string] : string}

const organization: Org = {}

organization.name = "Freecodecamp"

At the time the organization variable is declared, you go ahead and explicitly type it to the following {[key: string] : string}

To explain the syntax further, you might be used to object types having fixed property types:

type obj = {

name: string

}

However, you can also substitute name for a “variable type”.

For example, if you want to define any string property on obj:

type obj = {

[key: string]: string

}

Note that the syntax is similar to how you’d use a variable object property in standard Javascript:

const variable = "name"

const obj = {

[variable]: "Freecodecamp"

}

The Typescript equivalent is called an object index signature.

Moreover, note that you could type key with other primitives:

// number

type Org = {[key: number] : string}

// string

type Org = {[key: string] : string}

//boolean

type Org = {[key: boolean] : string}

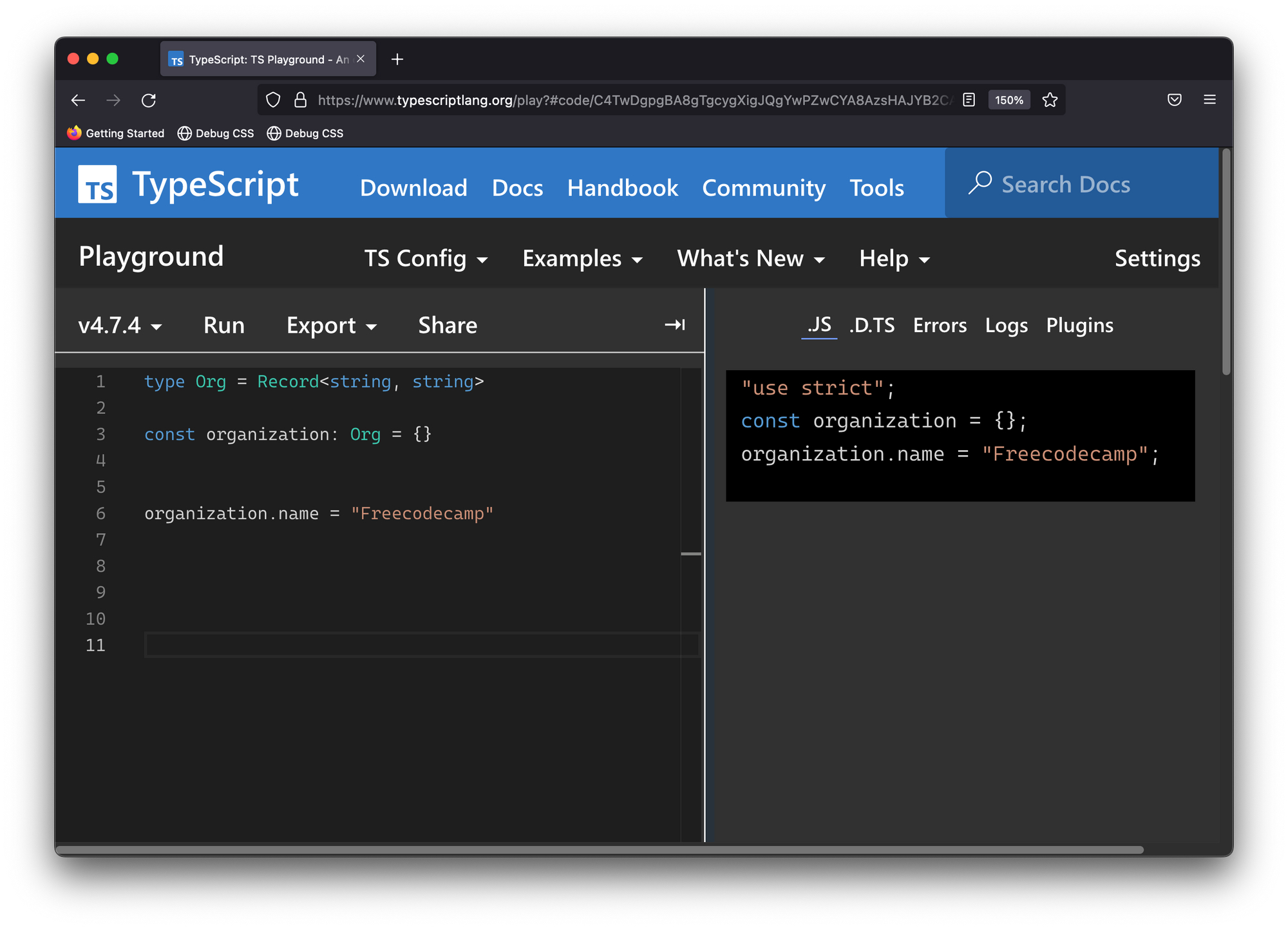

3. Use the Record utility type

The solution here is quite concise:

type Org = Record<string, string>

const organization: Org = {}

organization.name = "Freecodecamp"

Instead of using a type alias, you can also inline the type:

const organization: Record<string, string> = {}

The Record utility type has the following signature: Record<Keys, Type>.

It allows you to constrict an object type whose properties are Keys and property values are Type,

In our example, Keys represents string and Type, string as well.

Conclusion

Apart from primitives, the most common types you’ll have to deal with are likely object types.

In cases where you need to build an object dynamically, take advantage of the Record utility type or use the object index signature to define the allowed properties on the object.

Note that you can get a PDF or ePub, version of this cheatsheet for easier reference, or for reading on your Kindle or tablet.

Fancy a Free Typescript Book?